The combination of successful intuition, scientific knowledge and entrepreneurship enabled the doctor and humanist Mattioli and his Venetian publisher Valgrisi to make Commentarii to Dioscorides the best-selling scientific book of the Renaissance, as well as one of the most beautiful.

A century-lasting success.

There is no doubt that the Discorsi by Pietro Andrea Mattioli (his commentary on Dioscorides) was the greatest bestseller of Renaissance science. At a time when a book selling 500 copies was a success, the work of the Siena physician, in the thirty years between the first edition and the death of the author (1544-1578) sold 32,000 in its various versions. It was an unprecedented success, sought with tenacity by the author, enriching each new version with new plants and more and more detailed notes, by the skillful Venetian publisher Valgrisi, who benefited from a network enabling him to reach out to many European countries and by their powerful protectors, including the Emperor himself.

In the Middle Ages Dioscorides’ De materia medica had certainly not been forgotten, but circulated in more or less spurious versions. With the Renaissance and the birth of philological science, scholars competed to recover the original text, translate it, comment it: an enormous line of studies that culminates with the work of Mattioli.

He began translating Dioscorides’ work around 1541, adding his “discourses” or commentaries to the original text. The first edition (Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo Libri cinque Della historia, & materia medicinale tradotti in lingua volgare italiana da M. Pietro Andrea Matthiolo Sanese Medico, con amplissimi discorsi, et comenti, et dottissime annotationi, et censure del stesso interprete) comes out in Brescia in 1544 and is already much more than a simple translation because each entry is accompanied by a rich commentary on the identification of the specimen (with criticism of botanists who had preceded it), the description and the medical uses.

It is with the second edition in 1548 that the collaboration with the publisher Valgrisi began. At that moment the book, already much enlarged, started becoming a masterpiece in which the pages of Dioscorides are overwhelmed by the learned and meticulous commentary. The success was such that the same year a pirate edition was published in Mantua enriched with illustrations stolen from a German herbarium. Then Mattioli and Valgrisi understood that, to break through the European market, the work had to include and, of course, translated into Latin. In order to beat the German competition – the magnificent De historia stirpium by Fuchs is from 1542 – the illustrations had to be of exquisite quality.

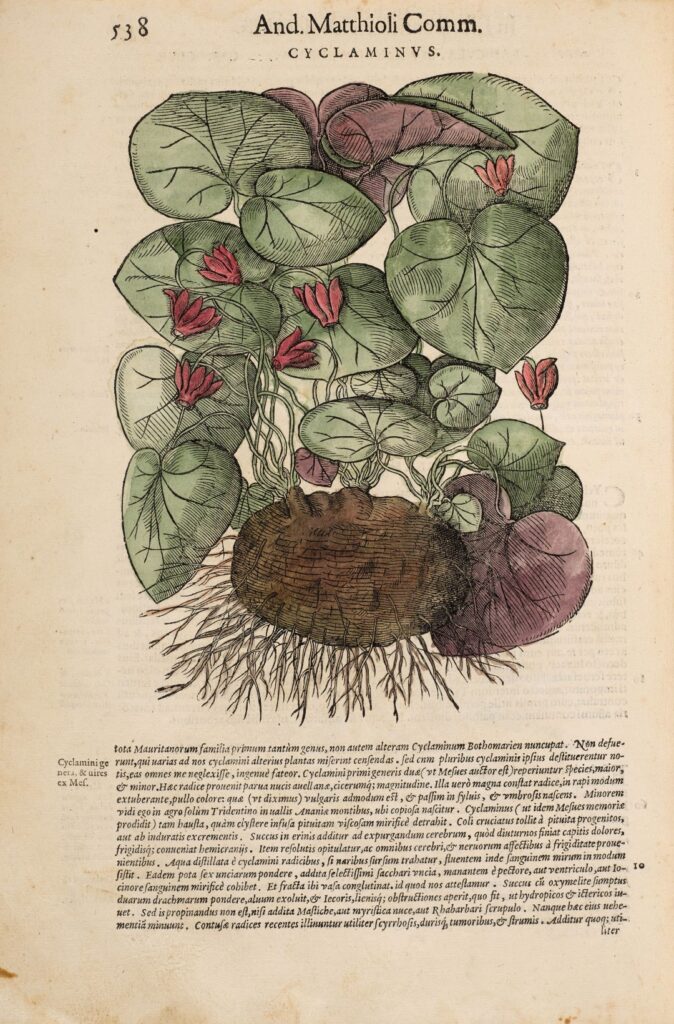

The task is entrusted to an excellent painter from Udine, Giorgio Liberale, who had some experience of naturalistic illustration having executed a series of drawings of animals for the emperor Ferdinand I. Even without the absolute precision of the plates accompanying Fuchs’ book the 562 illustrations by Liberale are of great aesthetic quality and elegance. The illustrated Latin edition, further increased compared to the second Italian edition, was published in 1554 (Petri Andreae Matthioli Medici Senensis Commentarii, in Libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei, de Materia Medica, Adjectis quàm plurimis plantarum & animalium imaginibus, eodem authore), obtaining great success and obtaining huge profits for the printer.

That golden mine was skillfully exploited in the following decade with three new editions for both the Italian version (Discorsi) and the Latin one (Commentarii) and numerous reprints, each with an average circulation of three thousand copies (exceptional figure for the time, when a circulation of 1000 copies was rare).

At that time Mattioli was called to the imperial court as a physician. In Prague, seat of the court, in a edition in Czech language is published in 1562 with 810 woodcuts, much larger and more elegant than those of the Valgrisi editions, made under the personal guidance of Mattioli da Liberale and Wolfgang Meyerpeck, an artist from Fribourg, assisted by some painters of the imperial court. Of great beauty and technical virtuosity, the woodcuts by Liberale and Meyerpeck do not aim so much at the accuracy of botanical illustration as at the transformation of nature into a work of art.

Thus, Mattioli’s Commentarii, in addition to imposing itself as the compulsory textbook in the faculties of medicine throughout Europe, also become a sought-after collector’s item. The woodcuts of the Prague edition are reused for the German edition of the following year and in 1565 Valgrisi inserts them in a wonderful edition of the Commentarii, printed on green paper. A precious copy, hand colored and decorated with gold and silver is donated to the illustrious protector of Mattioli, Emperor Ferdinand I. Other editions will follow, sometimes with the more handy illustrations of the first Latin edition, sometimes with the most spectacular ones of the Prague edition, with the work’s success going far beyond the death of the author (1578).

The reasons for success

What are the reasons behind such a glorious success? The beauty of the illustrations and the accuracy of the typography certainly played a major role; another factor is the encyclopedism of the work, which was seen by contemporaries as combining the knowledge of antiquity (from Dioscorides to Pliny to Galen) with the contributions of the popular herbal tradition and the acquisitions of Renaissance medicine. In fact, in the Discorsi and Commentarii the text of Dioscorides is only a starting point, a pretext, on which Mattioli pours all his knowledge as a philologist and scholar of antiquity, a doctor and a connoisseur of plants. To the little information of the Greek text, Mattioli adds meticulous descriptions of each plant (sometimes recognizing and discussing different species), the indication of the habitat, the medicinal virtues; there is no lack of practical indications and intriguing anecdotes.

Besides, Mattioli did not content himself with presenting the plants (in additional to animals and minerals) treated by Dioscorides, but gradually added new plants arriving in Europe from the Americas and the Near East or being discovered in Europe by the many botanists with whom he corresponded. The number of described plants doubles from the 600 analyzed by Dioscoride to the 1200 of the last editions of Mattioli; hundreds of new plants are described for the first time (we could mention tomato, sunflower, lilac) making the work an indispensable consultation text for every physician and botanist up to Linnaeus and beyond.

Our collection includes the first Latin and first illustrated edition of 1554, the second Latin edition with large woodcut (1585) and the third Italian edition with large woodcuts (1604), all in contemporary bindings.

Acknowledgements go to researches by Ilaria Andreoli and Silvia Fogliato.